By C. W. MIXTER, Associate Member of the Society

Abstract of a paper read at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 5, 1914

The idea of the writer’s modification of task and bonus is to accept that method as sound in principle, but to so redesign it as to afford greater satisfaction to the workers and lessen the expense of the employers. These remarks are intended to apply only to typical or prevailing conditions of industry as carried on under Scientific Management.

Jobs on task and bonus under Scientific Management fall into two classes. (1) Jobs with respect to which we feel most certain as to the accuracy of the time allowed, and (2) jobs fit for task and bonus, but with respect to which we feel less confident as to the accuracy of the time allowed.

Under ordinary day wage, if a man should perform a job in two hours and then go home, the time for which he would be paid would obviously be but two hours. If he did the job in three hours and went home, the time for which he would be paid would be three hours. The more time he takes, the more time he is paid for. Contrariwise, should he regularly work all day but gradually shorten the time for performance of this job from eight hours to six, to four, to three hours, etc., the time paid for doing this particular work would be constantly less in exact proportion to the lesser time taken. This brings out the fundamental defect of time wage; the workman works entirely for his employer and not at all for himself. All the gain from time saved on jobs goes to the employer, and the workman has no direct incentive for taking up slack. The method longest and most widely in use for taking up slack is the piece rate method which is at the opposite extreme from the day wage, so far as reward for fast work is concerned. All advantage of gain from time saved on a job, so far as wage cost is concerned, goes to the workman.

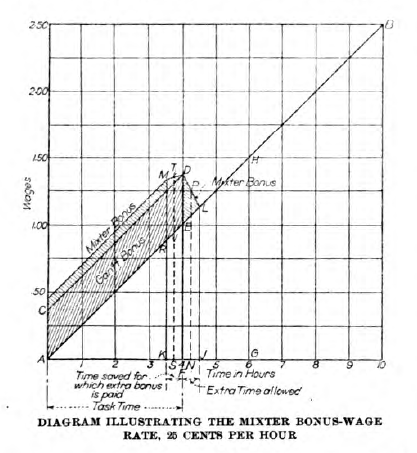

To obviate the disadvantages of day rate and piece rate, various systems of wage payments have been adopted, the more prominent among them being the premium system, the task and bonus method, and the Taylor differential piece rate. It is with a modification of the Gantt bonus method that we are concerned here. Under the Gantt bonus, the man is guaranteed his daily wages for the time spent on the job, irrespective of whether or not he accomplishes the job in the time allowed. This is illustrated graphically in the diagram Fig. 1. The diagonal line, AB, represents the daily wage line; the horizontal axis in the diagram represents time spent, while the vertical axis represents wages paid.

If a task is set for a workman to occupy four hours and he accomplishes it in that time or less, he receives in wages the equivalent value of his daily wages for four hours plus an additional bonus of 33%, or 1⅓ hours.

The objection which the writer has experienced to the use of the Gantt bonus is that there is a sharp demarcation between accomplishment of the task and failure to accomplish it. If the workman exceeds the task time by ever so little, he is penalized in that he loses his bonus and is paid only the regular daily wage for the time expended. It is, as it were, that the workman is climbing a hill represented by the line CD in the diagram and is required to finish the task before he reaches the point D. If he fails to accomplish this task he falls over the precipice at D and suffers injury exactly as he would did he fall over a real precipice, in that he loses a certain reward for work done.

It has been observed that workers under the Gantt system, who find themselves well within the task time will work at their top speed. On the other hand, workers who are closely approaching the task time, will not exert themselves particularly to reduce their time, as the reward for so doing is not sufficiently greater than that for just accomplishing the task to make the special effort attractive. Following this reasoning still further, it has been found that some workers who find that they cannot complete the task in the allotted time will deliberately slow down and consume as much time as possible without getting into trouble with their superiors.

To obviate this tendency on the part of the workers, the modification of the Gantt bonus described below, has been proposed by the writer. The principle is shown in the diagram herewith. It comprises a gradually decreasing bonus for the worker, who exceeds the task time up to a limit of 10, 15 or 20 percent, as the case may be; after which the worker will be paid at only his regular day wage rate. For the worker who performs a job in less than the task time, an increase in the bonus is provided which, in the case shown, has a maximum of 10 percent of the Gantt bonus. This maximum is reached when the worker shortens the time to a point where the time saved is equal to the excess time allowed over the task time before the worker begins to earn only day wages. That is, if a decreasing bonus is allowed for a period in excess of the task time equal to 10 percent of the task time, then an increasing bonus over the Gantt bonus is provided for all time saved up to 10 percent of the task time. For any saving beyond this 10 percent, the worker is paid the task time plus the Gantt bonus of 33 percent plus the writer’s modification of 11 percent. This method, it is believed, will compensate for errors in the time study or for conditions over which no control can be exercised and of which time studies cannot take cognizance. For instance varying temperatures, varying rates of humidity in the atmosphere, and similar conditions, which may or may not affect the time in which the work can be done. Thus, if a job is in hand, the time of performing which may be affected by the humidity of the atmosphere, a time study taken on an extremely dry day will not necessarily give the proper time for the same job if performed on a day when considerable moisture is present in the atmosphere. It would be obviously unfair to penalize the employee for failure to accomplish the task under these conditions and yet under the Gantt bonus, he would be so penalized.

Referring again to the diagram, which is intended only to outline the writer’s modification, the variation permitted over the task time is represented on the diagram by distances FJ and FK, in this case each being 10 percent of the task time. A man requiring the time AJ for his work will be paid an amount represented by the line LJ, or at his daily wage rate. For work accomplished in a time less than AJ, but greater than AF, as AN, he will be paid an amount represented by the line NP, of the distance between the base line AJ and the line joining points D and L.

For those employees who perform the job in less than the task time in the case under consideration, a gradually increasing bonus whose maximum is 10 percent. of the Gantt bonus, is paid. For a saving of 10 percent. or more, for instance, an elapsed time represented by AK, the man would receive a daily wage represented by FE, plus a bonus represented by the line MR. For a time less than AF, but greater than AK as AS he would receive a daily wage of FE plus a bonus represented by the line TV or the distance between the daily wage line and the line joining points M and D.

[Editor’s Note: Professor Mixter’s original paper comprised about 12,000 words and 8 diagrams. In order to publish it in the space available in the Bulletin, it has been necessary to abridge it as above. Those desiring to examine the entire paper, will find it on file at the office of the Secretary.]

PROF. ROBINSON: The objection that Prof. Mixter’s method interferes with fixing costs seems rather fallacious. Even if the worker is always paid the same rate per piece, if he does more at one time than at another the overhead changes, so that the real cost is subject to change anyhow.

The whole theory of Prof. Mixter’s plan is based on human nature. It is based on the fact that people are not alike. It is impossible to get together a set of workers who will all do the same job in the same time.

Even the same worker will vary in his speed from day to day and from season to season throughout the year. It is one of the established principles of Scientific Management that every man shall earn his bonus, that is of course after a reasonable time spent in learning how to do the job. If there are twenty men working all on the same sort of work and they have all become fairly skilled and are all expected to earn their bonus, then it follows that the task must be set so that the slowest man of the twenty can earn the bonus. It seems certainly obvious that some of the workers would be able to do considerable more work than the slowest man.

J. C. REGAN: Having in mind that an allowance over the time shown by the time study is made for the whole job, it seems to me unnecessary to take into account so keenly any variations that are in the worker or in the conditions that exist. If we are all looking for something to fix our piece price, we must have it within a reasonable limit, and therefore, you should be able to guarantee it, for a year or two years or three years.

It would be a fatal mistake in any business to penalize the better workmen by decreasing the bonus, as has been suggested, as the time consumed on a job is diminished considerably below the task time. Why not establish an acceptable labor cost standard and maintain that? Why say anything about the speedy workers? Why not let them get all they can? If the time study is at all near right, you should make money.

H. V. R. SCHEEL: We have one kind of winding machine, having 36 winding spindles on a side. The yarn run by operatives on these machines is of varying size, count or weight. The theoretical number of spindles on the various counts which an operator can run at standard efficiency has been determined, varying perhaps, from 14 spindles to 40 spindles, but the exactly correct number of spindles an operator can run cannot be assigned to each operator, so all of the yarns are roughly grouped into two classes: (1) Those which can be run on 18 spindles, and (2) those on 36 spindles.

Again, sometimes yarn is run from full spools and sometimes from partially full spools, the task being stiffer when small pieces are handled. Accordingly it sometimes happens that one of two operators on a side is running a count of yarn which normally takes 14 spindles, leaving 4 extra spindles available for her neighbor, who perhaps is running a count of yarn (and may be from full spools) which will permit her using these four spindles and doing a good day’s work turning off perhaps 16 or 18 hours’ work in 10 hours, with the result that the amount of earnings runs up as Prof. Mixter outlines. I think Prof. Mixter’s modification would be fair and without the objection which the present system has.

MR. REGAN: If the condition was constantly varying and you knew it had to vary, that would be all right. But with the general run of the time studies made, in the metal trades, the only constant to consider is the constant of hardness in the material, and also variations encountered in assembling, due to machining.

The condition you speak of is one which is met in that field to which you refer; however, is it true of studies, generally?

There is no doubt that we will always find conditions that have to be cared for as we meet them, but suppose we had a case which involved 150,000 to 200,000 rates or piece prices, would it be practical to consider a re-adjustment or re-arrangement every day, as under the Mixter plan, especially when each job may not last more than 6 or 8 hours, and the rate may be as low as 20 cent per 100 dozen?MR. KENDALL: I should like to ask how Prof. Mixter’s scheme will differ from the point of view of the workman, from the differential piece rate? That seems to me to be arriving at the differential piece rate through the means of the Task and Bonus, instead of arriving at it through the usual method of the old-fashioned piece-rate corrected with a stop watch, and then made into a differential. It seems to me Prof. Mixter is arriving at the same thing, only he starts from the Task and Bonus, whereas the differential piece-rate started at the piece-rate, possibly corrected by the stop-watch.